The Black Hole of My Mind: Discovering Aphantasia as an Ayahuasquero

A Visionary Who Can’t Visualize

I’ve always thought of myself as an ultra-visual person—by proxy, a visionary. My dream life is rich and vivid, I do have profound visions in ceremonial contexts and have tripped balls in my youth, and when insights and songs come they usually arrive fully formed—like downloads from the clarity stream. But recently, I had a realization that completely shattered my perception of how my mind works:

I can’t visualize on command.

If someone tells me to picture a box, I don’t see it. My mind is black. Guided meditations that ask me to “imagine myself on a beach” don’t produce any imagery—I experience them more as concepts or thoughts rather than visuals. I can calm my intellect to the point of occasionally seeing a wash of colors or light but that’s it.

I always thought this was the norm—how everyone’s brain worked. Turns out, that’s not the case at all. The majority of people actually see mental images when they visualize. They can construct entire scenes in their mind’s eye, shifting objects, colors, and perspectives at will. Meanwhile, I’m standing in a pitch-black void, trying to make something appear that never does.

I’ve been in a relationship with my wife for 14 years. She’s a Pisces. So I always chalked up her detailed visualizations to a Piscean gift of imagination. But actually, she’s normal. This is how the majority of you are.

Recently, I was synchronistically led to a Reddit post that made me realize I likely have aphantasia—the inability to voluntarily generate mental imagery.

My mind: fucked.

The Great Aphantasia Mind-Fuck

Here’s where my brain really started to melt: If I have aphantasia, then that means most people are walking around having psychedelic experiences all the time. They close their eyes and—bam—there’s a movie playing in their head. They can create entire worlds in their mind at will. And the craziest part? They take this for granted.

I always thought that when people talked about “seeing something in their mind,” they were speaking metaphorically. But no. They literally see it. And all this time, I had no idea.

It’s like waking up one day and realizing the sky has been a different color for everyone else this whole time.

If most people are generating imagery on command all the time, it’s no wonder they sometimes get confused about what’s a vision and what’s just "in their head." I never understood that struggle—because for me, if I see something, it’s extremely meaningful.

Maybe this is why I felt an undeniable pull toward visionary work with plant medicine in the first place.

Two decades of ceremonial experiences have allowed me to receive direct visions—though not on every single occasion—that were profoundly relevant to my life, my understanding of the world, and my experience of higher planes of multidimensional existence. In addition, the dreamwork that occurs in samá (dieta) in the Shipibo-Konibo tradition has been incredibly insightful, not only for my training, for my work in ceremony, but also for life in general.

Yet, it’s a strange thing to realize about consensus reality when people literally pay me to help them both open and make sense of their visions. I have been trained to open worlds of multidimensionality, to navigate visions of geometric-language, to remain lucid enough to pass intricate spiritual tests within dreams, and to translate all of this in a digestible way for folks in the Global North.

And yet, I still can't picture a red apple on command. But… you… can. Do you realize how psychedelic that is?

The Difference Between Projecting and Receiving

This realization forced me to rethink what it means to be a visionary. If I can’t visualize on command, then why do my visions come in so clearly when I’m in expanded states—dreaming, meditating, or working with plant medicine?

The answer, I believe, is that my mind functions more like a receiver than a projector. For most people, visualization is an active process—they summon an image and manipulate it like a mental sketchpad. But for me, it's different—I don’t construct images; I download them. Instead of piecing together a scene in my head, I occasionally experience visions that emerge on their own.

This is a pattern I’ve noticed in others who experience aphantasia as well. While they struggle with deliberate visualization, many report strong intuitive or psychic abilities, powerful dream imagery, and spontaneous flashes of insight. Some even excel at remote viewing or telepathic experiences because their perception isn’t clouded by imagined visuals.

This completely shifts the narrative around aphantasia. It’s not an absence of vision—it’s just a different mode of seeing.

Aphantasia, Psychic Abilities, and Visionary Thinking

As I explored this more, I started seeing the correlations between aphantasia and heightened intuition, claircognizance (clear knowing), and spontaneous visionary experiences. Here’s what I found:

Conceptual vs. Visual Thinking – Many people with aphantasia process information through deep cognition rather than imagery. Instead of seeing an outcome, they sense it, know it, or feel it energetically. This aligns with how many intuitive and psychic abilities work—not through mental projection, but through direct reception of information.

Spontaneous Imagery in Dreams and Altered States – Despite struggling with visualization in waking life, people with aphantasia often report hyper-vivid dreams, spontaneous visions, or lucid experiences. This suggests that their minds can generate imagery, but only when the conscious mind steps aside.

Less Prone to False Memories – Some studies suggest that aphantasic individuals are less likely to create false memories because they don’t generate visual reconstructions. This could mean they are more accurate in psychic perception, remote viewing, or intuitive insights—since their minds don’t overlay mental projections onto an experience.

This completely reframes what it means to be a seer, a mystic, or a visionary. It suggests that conscious visualization isn’t the only way to access non-ordinary perception—some of us are wired to receive rather than construct.

While these ideas are fascinating and worth further exploration now that we’re no longer self-deprecating and calling real things woo, the phenomenon of aphantasia has actually been studied for over a century.

The History of Aphantasia

The term aphantasia was first coined in 2015 by cognitive neurologist Adam Zeman and his research team at the University of Exeter. While cases of people lacking mental imagery had been documented before, Zeman's study formally identified and named the condition, bringing it into mainstream awareness. His research was initially inspired by a patient who reported losing the ability to visualize after a medical procedure, leading Zeman to explore the phenomenon further.

Though the term is new, descriptions of individuals with aphantasia date back centuries. In the 1880s, Sir Francis Galton—Charles Darwin’s cousin—conducted one of the earliest studies on mental imagery, noting that some people seemed unable to form visual images at all. However, his findings were largely ignored for over a century until modern neuroscience revisited the topic.

Understanding Aphantasia (Or, Why My Brain is a Black Hole for Apples)

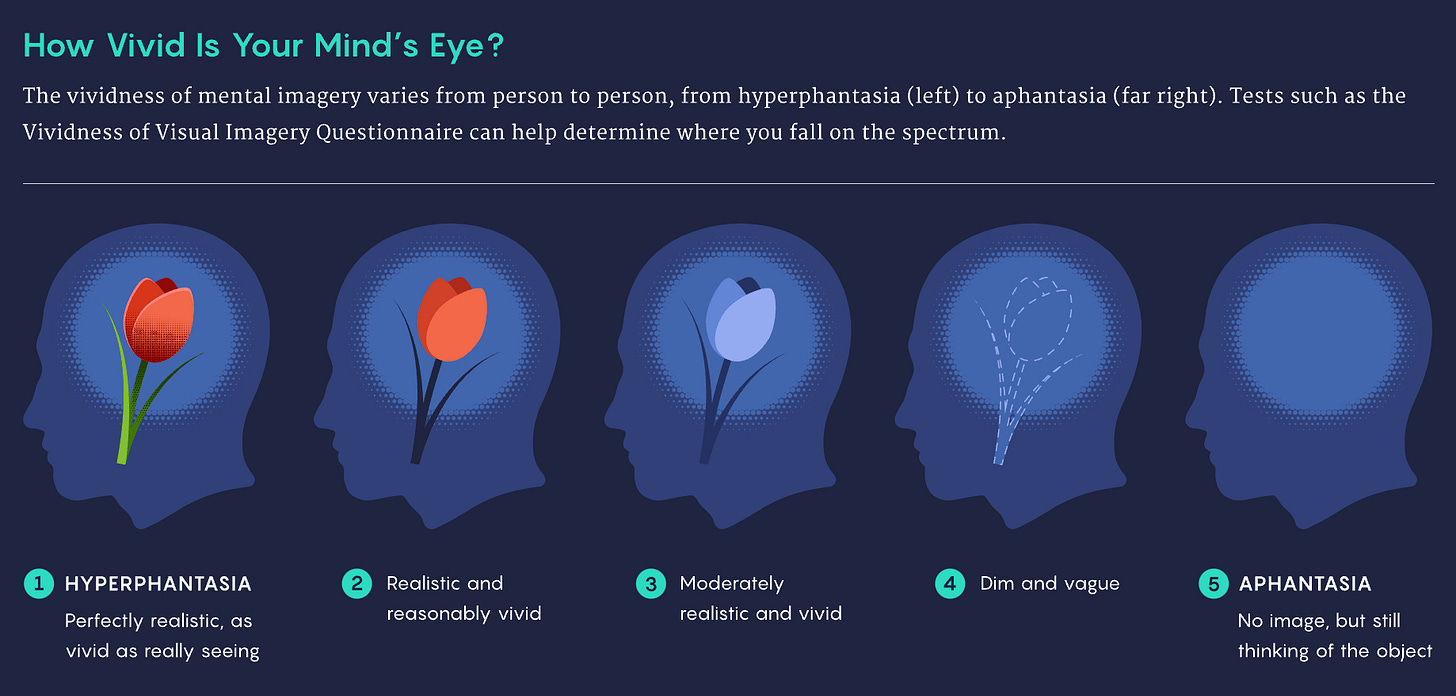

Aphantasia exists on a spectrum, and here’s how it breaks down:

Aphantasia: Complete absence of voluntary visual imagery. No

box. Noapple. Nobeach. Just vibes.Hypophantasia: Somewhat vague or dim mental imagery. Like trying to remember a dream right after waking up.

Typical Imagery: The default setting for most people—clear but not overwhelming mental pictures.

Hyperphantasia: High-definition, 4K, IMAX-level mental imagery. People with this can close their eyes and see an apple so clearly they could practically take a bite out of it.

Research suggests that 1-3% of people have aphantasia while about 5-10% have hyperphantasia—meaning most people fall somewhere in the middle. And yet, nobody talks about this. How did we all go our whole lives assuming we experience reality the same way?

Multisensory Aphantasia: More Than Just Mental Imagery

For some, aphantasia isn't just about the inability to visualize—it's multisensory, meaning they also lack internal representations of sound, touch, taste, or even spatial awareness. I, for one, can’t summon mental images, smells, tastes, sounds, or recreate sensory experiences on demand.

Some people with multisensory aphantasia report:

Auditory aphantasia – They can’t “hear” music in their heads, even if they are musicians.

Tactile aphantasia – They can’t mentally recall the feeling of textures or sensations like warmth or pain.

Olfactory & gustatory aphantasia – They can’t “imagine” smells or tastes, even if they vividly remember experiences associated with them.

This raises fascinating questions about how memory, perception, and imagination function in different brains. If I can’t summon a sound or an image in my mind, does that mean my memory is purely conceptual? If I do have a deep connection to sound and rhythm, does that mean my brain has naturally compensated by amplifying my auditory awareness?

The Urge to "Fix" Aphantasia

A surprising thing I discovered is that many people, when they first realize they have aphantasia, immediately start searching for ways to cure it—as if it’s a defect rather than just a different way of processing reality. There are entire Reddit threads and forums filled with people trying everything from psychedelics to hypnosis to “activate” their mind’s eye.

I’ve done over a thousand ayahuasca ceremonies, thirty-some-odd dietas and nothing has “cured” the black screen of my mind (that I wasn’t aware wasn’t normal until a few weeks ago).

Because, what if aphantasia isn’t something that needs fixing? What if, instead of trying to force ourselves into a way of thinking that isn’t natural, we leaned into our strengths? It seems actually that people with aphantasia tend to excel in conceptual thinking, pattern recognition, and direct knowing. It’s not that we can’t see—it’s that we see differently.

Non-Visual Thinking

How does aphantasia affect cognitive processing? People with aphantasia are often better at abstract reasoning and rely more on linguistic or conceptual thought rather than visual memory.

I can’t see faces or places in my mind, but my sense of direction is incredibly instinctual—almost psychic. While I don’t “see” memories, I occasionally experience dream recall in a way that feels like an astral overlay on waking reality—fainter, but still present.

Does the brain compensate for the lack of mental imagery with stronger auditory processing, enhanced logical reasoning, or a heightened ability to synthesize concepts? People with aphantasia tend to describe memory as knowing facts rather than reliving experiences. This could imply, as I stated already above, they are often less susceptible to false memories—their minds don’t reconstruct past events with mental images that can be distorted over time.

The Shock

I must admit even after researching the topic for a few weeks I’m still having a hard time believing it all. I’m a bit in shock. It makes me wonder what the purpose of those with aphantasia might be? For me, now, it feels almost as my role as a guide to waking people up to their multidimensionality has taken on a whole new level of weight. Again, you can project images on command and you don’t realize how incredibly multidimensional that is because you take your own imagination for granted.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mercuria to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.